UK immigration from Africa witnessed a boom between 2021 and 2024 as about 525,000 Africans from Nigeria, Ghana and Zimbabwe alone, arrived in the United Kingdom on study and work visas. But beyond the exodus, emerging migration patterns show the extent of the growing contribution by African nationals to the UK’s labour force and higher education system.

- Visa Growth: UK Immigration from Africa by Study and Work Routes

- Caregiving and the African Workforce: A Growing Driver of Migration

- Education as a Launchpad for Long-Term Migration

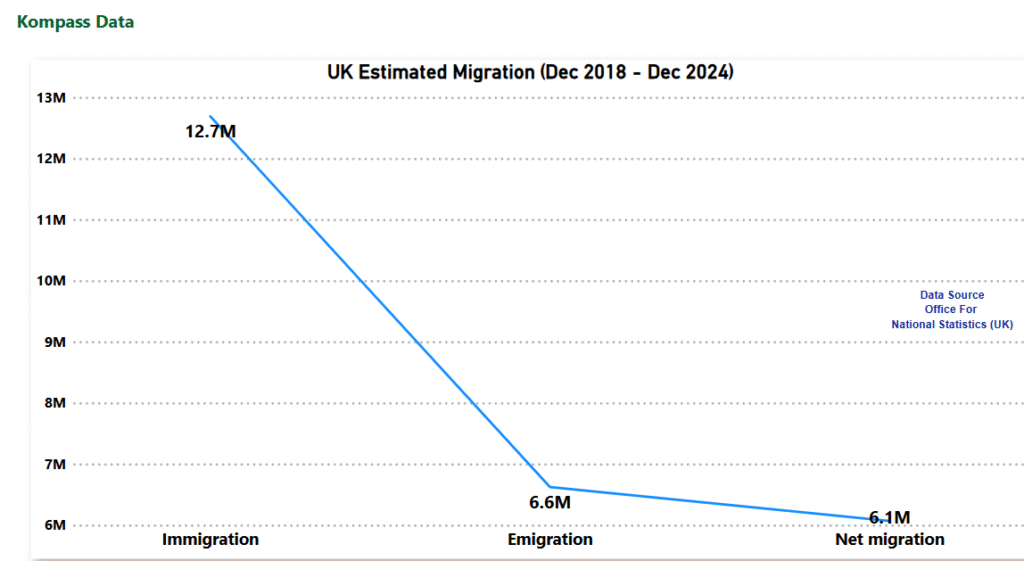

- Immigration vs. Emigration: Who’s Coming In and Who’s Leaving?

- Net Migration: A 6.1 Million Increase from 2018 to 2024

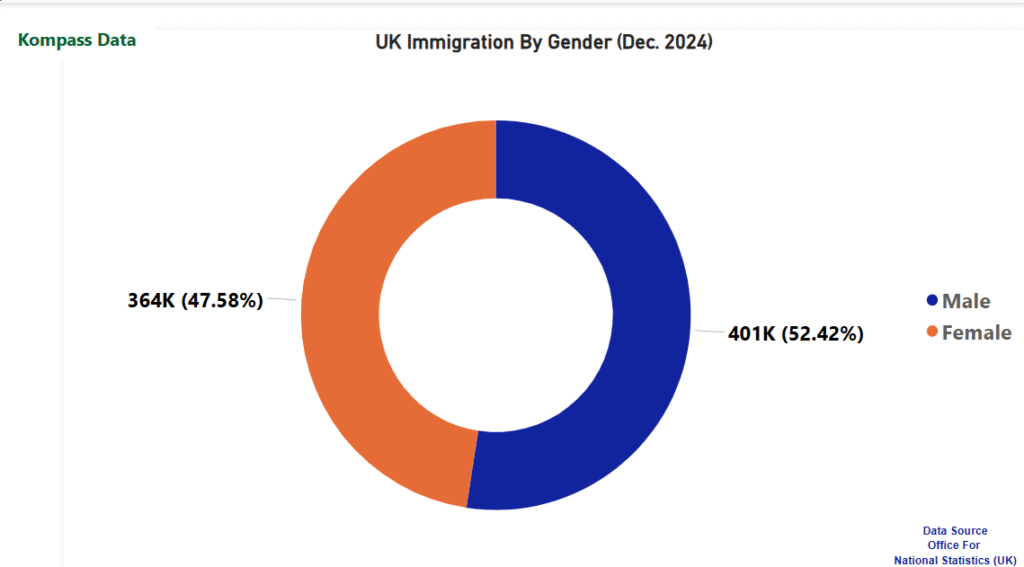

- Gender Shifts: The Rise of African Women in UK Labour Migration

- Challenges for Africa: Brain Drain vs. Remittance Gains

- Work Visa Applications in 2025

- Family Visa Applications in 2025

- Study Visas Applications in 2025

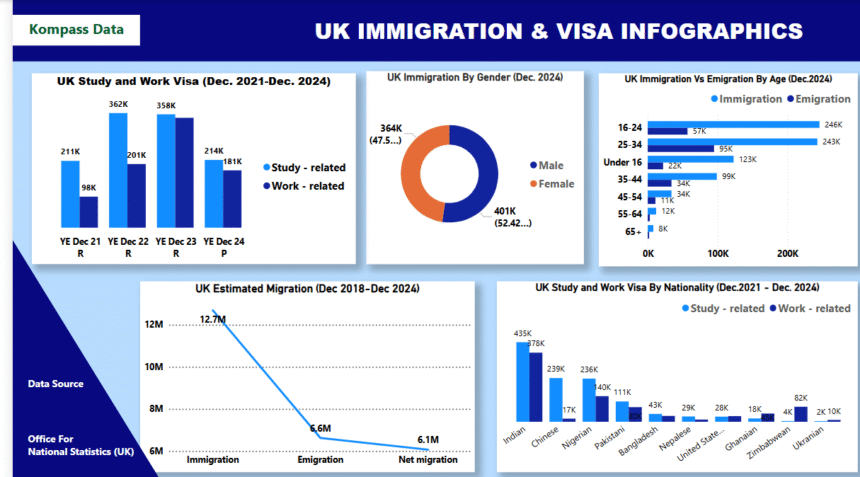

Newly visualised figures by Kompass Data, using the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) migration dataset, reveal shifts in visa issuance, age, gender, and net migration across countries sending immigrants to the UK during the period under review.

Driven largely by rising demand for higher education and labour in essential sectors, especially caregiving as UK population age, this trend spotlights growing links between African countries and UK’s changing demography, culture and economic priorities.

Visa Growth: UK Immigration from Africa by Study and Work Routes

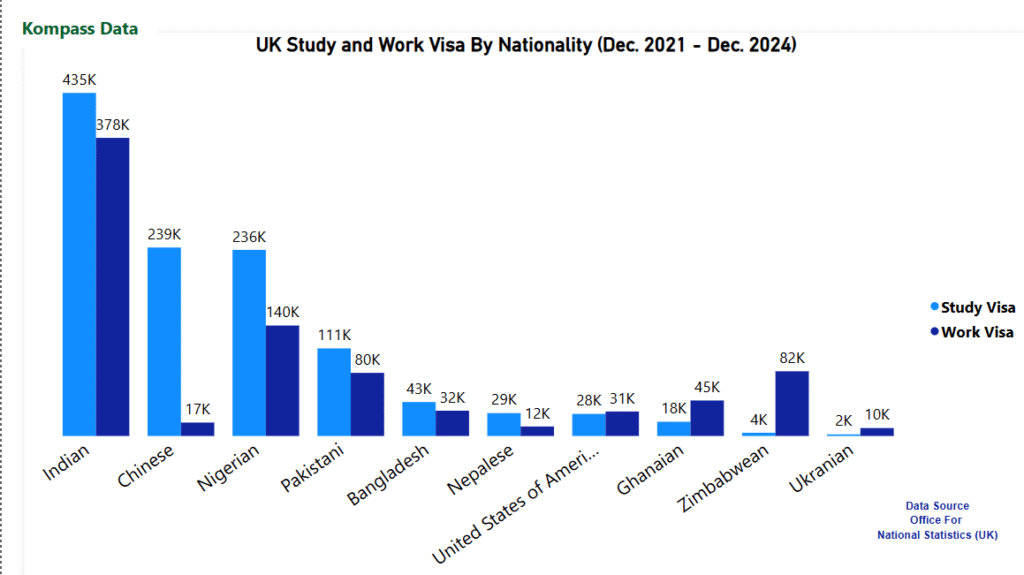

ONS data shows that from 2021 to 2024, the UK issued approximately 964,000 study visas and 908,000 work visas. While Indian nationals topped the list with 435,000 study and 378,000 work visas, UK immigration from Africa emerged as a major component, with Nigeria leading the African contingent by securing 236,000 study visas and 140,000 work visas.

This wave of migration captures the spirit of ‘Japa’, a popular Nigerian slang term derived from Yoruba language, meaning ‘to flee.’ Once a niche expression, it has entered mainstream usage to describe the mass departure of skilled young Nigerians, and increasingly, Africans, in search of better opportunities abroad. The UK has risen to the top of the immigration data in Africa due to shared language, historical ties dating back to the colonial era, and clearer post-study pathways.

Ghana and Zimbabwe also featured strongly. Ghanaians received 45,000 work visas and 18,000 study visas, while Zimbabweans secured 82,000 work visas but only 4,000 study visas, indicating more direct labour market entry rather than through education.

Caregiving and the African Workforce: A Growing Driver of Migration

One of the fastest-growing drivers of UK immigration from Africa is the demand in the caregiving sector. Chronic staff shortages in social care have prompted UK recruitment from abroad, particularly from Nigeria, Ghana, and Zimbabwe.

Many African migrants have entered via the health and care worker visa route, which includes roles such as elderly care, residential support, and hospital assistance. According to ONS figures and NHS workforce data, caregiving is now a top occupation for African work visa recipients.

This trend is also reshaping gender dynamics. More African women are entering the UK labour market in these essential roles, generating remittances for families back home while supporting a critical part of Britain’s social infrastructure.

Education as a Launchpad for Long-Term Migration

Pursuing international education remains a central reason for UK immigration from Africa. The graduate route visa, which allows international students to remain for two years post-degree, has made the UK more attractive to African applicants.

Despite costs often exceeding £30,000 per year in tuition and living expenses, many African families see UK education as a long-term investment. It often serves as a strategic entry point into the UK job market.

The UK benefits as well. Nigerian students alone contribute over £2 billion annually to the UK economy through tuition and living costs, according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA).

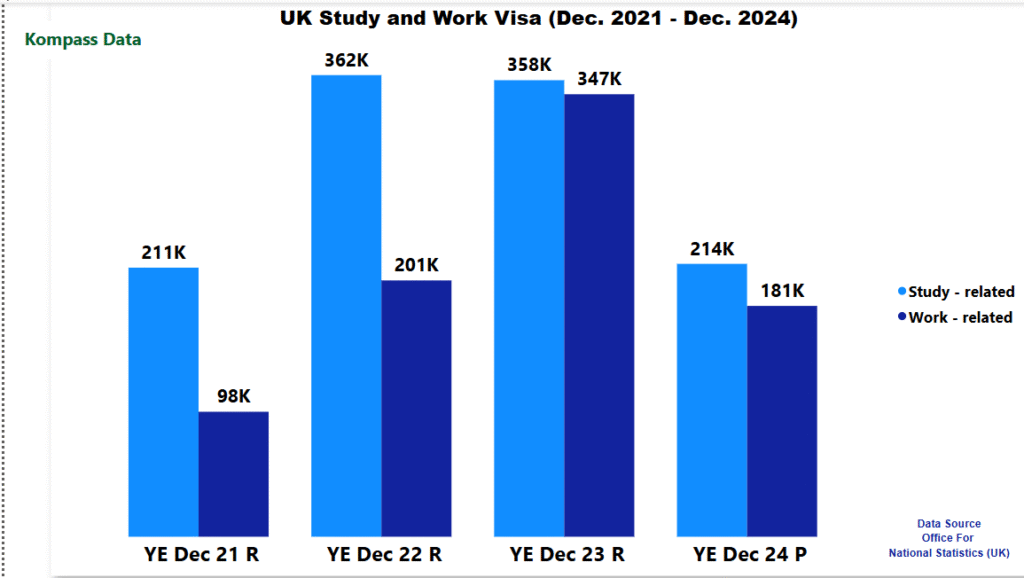

However, new restrictions such as barring dependants for most international students, is already impacting enrolments in no small way, especially from countries where students frequently migrate with spouses and children. As highlighted by Kompass Data, this became evident in the number of study visas issued by the UK in the year ending 2024 as it sharply dropped to about 214,000 as against the 358,000 approximately issued in the previous year-2023, before the government stopped foreign students from bringing family members to the UK. Only students enrolled in a PhD or research-based Master’s programme are exempted. Data also showed that many international students, including those from Africa turned their back on UK education since the policy kicked in on January 1st, 2024.

Immigration vs. Emigration: Who’s Coming In and Who’s Leaving?

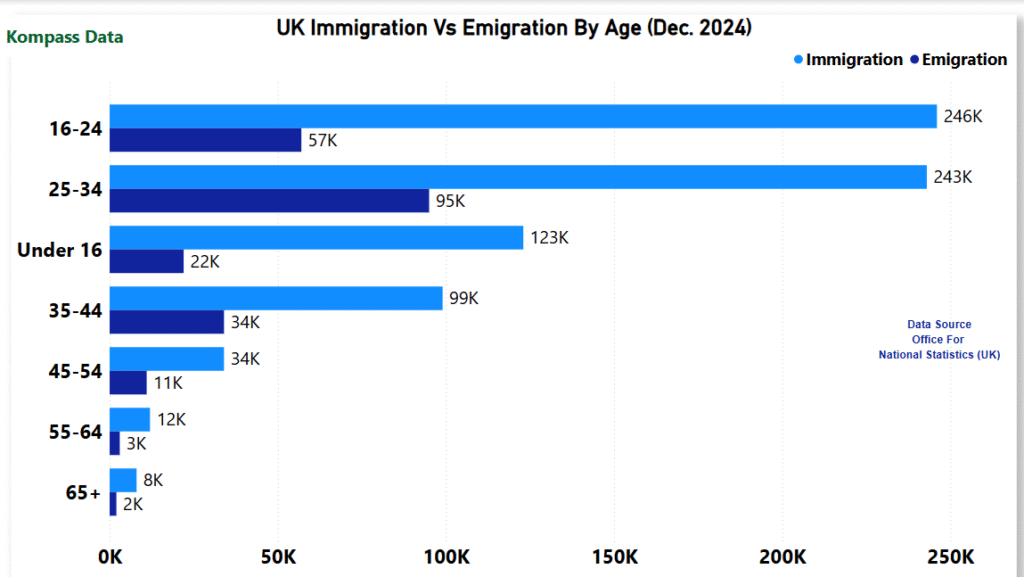

The migration balance is nuanced. In 2024, 246,000 people aged 16–24 and 243,000 aged 25–34 arrived in the UK. This includes many from Africa on work study and work visa those on work visa.

By contrast, 57,000 aged 16–24 and 95,000 aged 25–34 left the UK, including those finishing their studies and UK nationals emigrating abroad, many of them younger migrants, raising questions about the UK’s ability to retain global talent.

Net Migration: A 6.1 Million Increase from 2018 to 2024

According to ONS figures gleaned by Kompass Data, from 2018 to 2024, the UK recorded 12.7 million arrivals and 6.6 million departures, resulting in a net migration gain of 6.1 million. UK immigration from Africa played a growing role in this increase, particularly as demand for health workers and students intensified.

While critics and UK conservative politicians like Kemi Badenoch often argue that this growth strains housing and public services while expressing anti-immigrants’ sentiments, others note the essential contributions of migrants, particularly in healthcare, education, and care work as the lifeline upon which the UK economy currently stands.

Gender Shifts: The Rise of African Women in UK Labour Migration

Of the total immigrants to the UK in the year ending June 2024, male and female accounted for 52 percent and 48 percent respectively. The near balance reflects a shift from traditional male-dominated migration trends.

African women now make up a substantial part of the caregiving and healthcare workforce in the UK, filling roles that are vital to national well-being. Their presence underscores both the economic impact and gendered dimension of UK immigration from Africa.

Challenges for Africa: Brain Drain vs. Remittance Gains

For African governments, this outflow of skilled and educated youth raises tough questions. While remittances and diaspora networks are beneficial, losing talent, especially in fields like healthcare and tech, is a challenge to domestic development. This is already seen in Nigeria, where doctor-to-patient ratio has crashed to one doctor per 9,000 to 10,000 patients, far below the one doctor for every 600 patients recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

This also points to the imbalance between retaining critical workers and leveraging diaspora potential for African leaders.

Work Visa Applications in 2025

The UK Home Office has reported a 39% drop in work visa grants, with only 192,000 issued in the year ending March 2025, compared to the previous year.

The Health and Care Worker visa category has been hit hardest, with applications dropping from 18,300 in August 2023 to 1,300 in July 2025, an 85% decrease.

This collapse follows tightened employer scrutiny, increased compliance checks, and a ban on overseas recruitment for care roles introduced in spring 2024. Existing care workers in the UK can switch visas until July 2028, but new international applicants are barred.

Also, Pan-Atlantic Kompass checks revealed that skilled Worker visas saw a decline, with applications falling from 10,100 in April 2024 to 4,900 in July 2025.

Temporary work visas, such as the Youth Mobility Scheme (including the India Young Professionals Scheme), dropped 10% to 22,200 applications in the year ending July 2025. Meanwhile, Seasonal Worker visas rose 9% to 38,600, staying within the usual 30,000–40,000 quota.

Family Visa Applications in 2025

Family visa applications have also experienced fluctuating numbers due to new income requirements.

Applications surged from 7,500 in December 2023 to 12,700 in April 2024 after the government announced a higher Minimum Income Requirement, prompting a rush to file before the April 2024 implementation.

Post-implementation, applications fell to 5,100 in June 2024 but recovered slightly to 8,100 by July 2025. Annual family-related grants reached 76,000 in the year ending March 2025, down 3% from the prior year.

Study Visas Applications in 2025

In contrast, sponsored study visa applications for main applicants remained steady at 428,900 in the year ending July 2025, down just 3% from the previous year.

However, dependant applications plummeted 86% to 20,200 following a January 2024 rule change that restricts dependants to postgraduate research students or those with government-funded scholarships.

Kompass Data shows that UK immigration from Africa is now a core element of Britain’s international migration story. African youth, driven by ambition, constrained by local challenges, but supported by global mobility, are transforming societies on both sides of the Atlantic.

While this data represents a period of significant growth for the UK immigration and education market, it appears the outlook might be changing rapidly for ‘Japa’ enthusiasts as Pan-Atlantic Kompass digital magazine had copiously reported the implications of the ‘immigration white paper’ by the UK government, detailing measures to cut down immigration across the UK.

In May 2025, the UK government published a white paper titled “Restoring Control Over the Immigration System.”

This document outlined the most significant overhaul of the UK’s legal migration framework in decades, primarily aimed at reducing net migration (which hit record highs in previous years) and shifting the focus toward “contribution-based” immigration.

The White Paper moved the UK away from “broad-based” recruitment toward a system that prioritizes high-skilled workers and domestic labor.

The reforms are being implemented in a phased approach.

Below are some of the timelines as outlined in the White Paper;

May 12, 2025: Publication of the White Paper: “Restoring Control Over the Immigration System.”

July 22, 2025: Social Care Ban: Overseas recruitment of social care workers officially ended.

Dec 16, 2025: Skills Charge Increase: The Immigration Skills Charge (ISC) for employers rose by 32%.

Jan 8, 2026: English Proficiency: The requirement for Skilled Worker and HPI visas increased from B1 to B2.

April 2026: ILR Overhaul: Planned implementation of the new 10-year “earned settlement” rules.

Jan 1, 2027: Graduate Visa Cut: New applicants’ post-study work rights reduced from 2 years to 18 months.

August 2028: Student Levy: A proposed £925 annual levy per international student is scheduled to begin.

Key Details of the Reforms

1. Work Visas (Skilled Worker Route)

Skill Threshold: The minimum skill level for sponsorship is rising from RQF Level 3 (A-level equivalent) back to RQF Level 6 (Degree level). This disqualifies roughly 180 previously eligible occupations.

Salary Thresholds: Minimum salary requirements are being increased significantly to ensure migrants are not used to undercut UK wages.

Abolishing the Salary List: The “Immigration Salary List” (which allowed a 20% discount on salary thresholds for shortage roles) has been abolished and replaced by a more restrictive Temporary Shortage List.

2. The “Earned Settlement” Model (ILR)

The most controversial change is the shift in Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR):

Standard Path: The default time to qualify for settlement is doubled from 5 years to 10 years.

Accelerated Route: Migrants can still settle in 5 years if they meet “contribution criteria,” such as high salary levels, working in high-priority sectors, or specific community involvement.

New Requirements: Applicants must now meet a B2 English level and show a minimum personal income (proposed at £12,570) for several years.

3. Students and Graduates

Graduate Visa (Post-Study Work): The duration is being cut from 24 months to 18 months (PhD students remain at 3 years).

Student Levy: A new “International Student Levy” of £925 per year of study will be charged to help fund domestic skills training.

Compliance: Universities face tougher “Basic Compliance Assessment” (BCA) metrics, including a 95% student enrollment requirement.

4. Families and Dependants

English Requirements: For the first time, partners/dependants of work visa holders must meet a minimum English language requirement (A1 level).

Self-Sufficiency: Stricter financial checks to ensure family members do not rely on public funds.